Tick Encounters 2023

- P.K. Peterson

- Apr 12, 2023

- 4 min read

“People in eight states should know the signs of the tick-borne disease babesiosis as cases rise."

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

“Ticks suck!”

- TicksSuck.org

It’s spring and it’s again time to prepare for tick season. These pesky arachnoids (899 species strong) compete with insects, such as mosquitoes and fleas, as a major source of vector-borne infections. In this Germ Gems post, I summarize the tick-borne diseases that are of the most concern—some of which can be fatal—and provide advice on ways to avoid being infected by a tick in the first place.

Tick-borne diseases. As is true for many infectious diseases, geography (“location, location, location”) is critically important in determining what tick-borne diseases might affect you. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and your state’s Department of Health are excellent resources for this information (and for virtually everything else you might want to know about ticks).

If you live in Minnesota, the tick-borne diseases you’re at risk of acquiring in 2023 are:

Lyme Disease

Anaplasmosis

Babesiosis

Ehrlichiosis

Powassan Virus Disease

Borrelia miyamotoi Disease

Borrelia mayonii Disease

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

This list of tick-borne diseases is similar to the list one would find in the New England states. In both areas of the U.S., the tick species Ixodes scapularis, aka the blacklegged tick or deer tick, carries pathogens that cause the “big three” diseases: Lyme disease; anaplasmosis; and babesiosis. (It is also the vector for Powassan virus that kills between 10-15% of its victims.)

Babesiosis is the one tick-borne disease on this list that’s garnering more attention in 2023 than in previous years. (This is a change from “Tick Talk,” which was my first Germ Gems post on tick-borne infections in April 2021.) According to a March 24, 2023, article from the Mayo Clinic, “Babesiosis and what you need to know about the 2023 tick season,” there’s been a significant increase in reported cases of this parasitic infection in New England, including in states where babesiosis hasn’t been endemic, namely, Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. While symptoms of babesiosis range from none (asymptomatic) to a flu-like illness, it can be fatal (the mortality rate is about 20%). Thus, the CDC and relevant state Departments of Health are issuing alerts to primary care providers to be on the lookout for babesiosis in 2023.

Prevention of tick-borne infections. The CDC recommends these steps to guard against babesiosis as well as infection with other tick-borne diseases: avoid ticks in the first place; and if you find a tick, carefully remove it.

To avoid ticks:

Stay on cleared trails and minimize contact with leaf litter, brush and overgrown grasses, where ticks are likely to be found.

Minimize the amount of exposed skin. Wear socks, long pants and a long-sleeved shirt. Tuck your pant legs into the socks. Wear light-colored clothing, to make it easier to see and remove ticks.

Use tick repellents that contain DEET on your skin and clothing.

To remove ticks:

After being outside, check your body for ticks and remove any that are found.

Remove ticks from clothing and pets before going indoors.

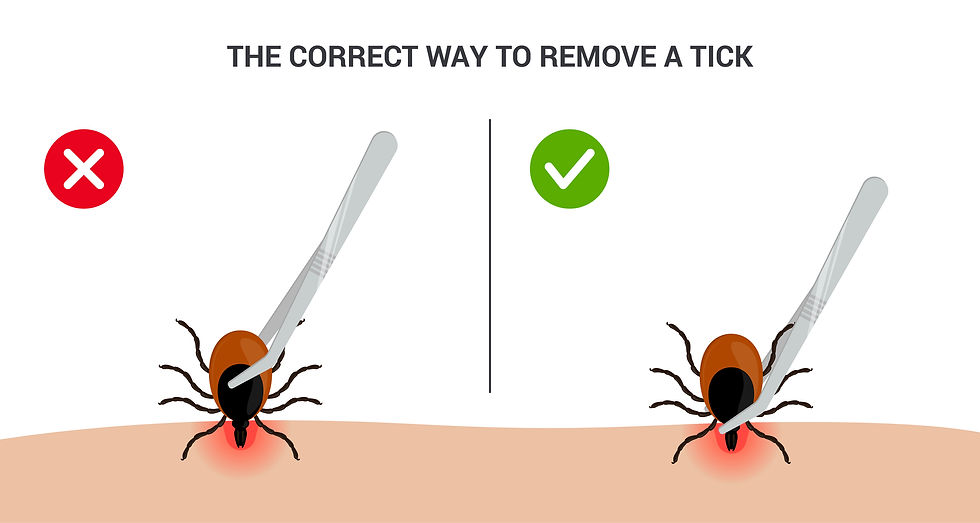

Remove ticks as soon as possible from the body by using pointed tweezers. Grab the tick’s mouth close to the skin, and slowly pull the tick straight out until the tick lets go.

If you are having trouble removing a tick, a rag soaked with hydrogen peroxide and held on the area for a few minutes makes ticks uncomfortable causing them to release their hold. The tick can then be grabbed and disposed of without yanking. Additionally, several Internet websites provide instructions on tick removal. I recommend the CDC’s “Tick Bite Bot” as a Tick Removal tool.

If you’re interested in the species of tick that you removed, you might visit the University of Rhode Island’s website, “TickEncounter.” It is an excellent resource for this information, as well as many other tick-related matters.

Follow-up after tick removal. Most tick bites are harmless. But depending on the geographic location, anywhere from less than 1% to more than 50% of ticks are infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. In areas that are highly endemic, the CDC recommends a single prophylactic dose of the antibiotic doxycycline (200 mg for adults or 4.4 mg/kg for children of any age weighing less than 45 kg) to reduce the risk of acquiring Lyme disease after a high-risk tick bite.

While doxycycline is highly effective for treatment of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis, it is of no value in the management of babesiosis—a disease that requires a completely different antimicrobial regimen. Therefore, whether you take prophylactic doxycycline or not, if you develop a rash or fever within several weeks of removing a tick, see your doctor for input regarding other tickborne infections to consider.

Walking in the woods. Mounting evidence suggests that connecting with nature is good for human health. (See International Journal Environmental Research Public Health, May 2021, “Associations between Nature Exposure and Health: A Review of the Evidence.”) So, as is the case for most, if not all, activities, the decision whether or not to go for a walk in the woods is shaped by an assessment of the risks versus benefits. If you follow the advice of the CDC or of your state’s Department of Health regarding prevention of tick-borne diseases, the scale weighs heavily in favor of a walk. It will benefit not only your physical health but your mental health as well.

Time to buy hydrogen peroxide and refresh the DEET bug spray! I didn’t know about babesiosis. I will print out the visuals - thank you!

very good